Description

5,000-acre Bábaco ranch, the purchase of which was supported by the Quick Response Biodiversity Fund to expand the Northern Jaguar Reserve in Sonora, Mexico. Photo by Miguel Gomez.

The benefits of land acquisition as a conservation strategy are obvious enough. If you own the land, you get to decide what happens to it — or what doesn’t happen to it, as is perhaps more often the case.

But when an opportunity to acquire some crucial piece of habitat becomes available, conservationists don’t always have the funds at their disposal to outbid other interested parties. And going through official channels to set aside protected lands can be a cumbersome process.

Enter the Quick Response Biodiversity Fund (QRBF), a new initiative whose goal is to rapidly respond to opportunities to purchase land in developing countries as a way to protect critical habitat for endangered and threatened species. The fund was launched in February by the New York-based Weeden Foundation and its grantee, the Vermont-based conservation group 1% For The Planet, which has built a network of more than 1,200 corporations that donate at least 1% of their sales to environmental causes.

Establishing protected conservation areas is a proven strategy. A study last year of more than 80 parks and nature reserves found they were not only home to more wildlife than unprotected neighboring lands, but that they provided habitat for a greater diversity of life as well.

“You buy the land so you can stop the bleeding, the dwindling of this habitat,” Weeden Foundation executive director Don Weeden told mongabay.com. “It stops the threats, and, for the time being, you can have it managed by an NGO.” This opens up a variety of long-term options, Weeden said, such as handing the land over to the government to be turned into a national park or preserve.

The important thing, of course, is being in a position to buy the land when it becomes available. Weeden said the idea for the QRBF came from seeing too many land-acquisition proposals languishing for months as the organization or foundation considering them worked through their own bureaucratic processes. “We felt sometimes you miss opportunities as a result,” Weeden told mongabay.com.

Land acquisitions work especially well for protecting endemic species, according to Weeden. Even a small parcel of land can make a big difference to their chances of survival, especially because this approach can be accretive, adding to existing protected areas or putting a new preserve together piece by piece.

“For endemic species, and often bird species, for instance, their habitat is not a large piece of landscape,” Weeden said.

An endangered Santa Marta parakeet takes flight. 148 acres of land that supports the bird’s largest breeding population was recently purchased with help from the new fund. Photo credit: Andy Bunting.

An endangered Santa Marta parakeet takes flight. 148 acres of land that supports the bird’s largest breeding population was recently purchased with help from the new fund. Photo credit: Andy Bunting.

He points to the endangered Santa Marta parakeet (Pyrrhura viridicata) as an example. The bird lives in a relatively small mountain range in Colombia called the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, which is being nibbled away by agricultural expansion and other disruptive human activities.

Recently, the QRBF made a grant to the conservation group the American Bird Conservancy to purchase 148 acres of partially forested land that supports the largest breeding population of Santa Marta parakeets. The land will be an important addition to the more than 2,000-acre El Dorado Bird Reserve that the American Bird Conservancy helped its Colombian partner, ProAves, establish.

ProAves has been negotiating the purchase of the new 148-acre parcel for the past five years. A recent change in the seller’s circumstances meant a lower asking price, but there was a catch — the deal had to be closed by April 15. So the American Bird Conservancy turned to the QRBF.

Because of how small the parakeet’s territory is, conserving just a few dozen extra acres of land will make a big impact. Dozens of other species will benefit, as well, including the endemic Santa Marta bush-tyrant (Myiotheretes pernix) and Santa Marta warbler (Myiothlypis basilica) and native palms where the parakeets feed and roost.

“An

An endangered Santa Marta parakeet. Photo credit: Andy Bunting.

In order to buy land to protect species like the Santa Marta parakeet, 1% For the Planet, with money from its member companies, provides the funds to local conservation groups, while the Weeden Foundation provides the expertise in land acquisition and conservation. The QRBF’s other key component is its advisory panel, which is made up of over 50 of the world’s top conservation biologists.

The panel’s chair is Eric Dinerstein, who is now the Director of Biodiversity and Wildlife Solutions at the environmental NGO Resolve after serving as Chief Scientist at the World Wildlife Fund for much of the past 25 years. (Resolve is Mongabay’s partner on the upcoming WildTech initiative, which will explore the use of emerging technology in conservation.) Dinerstein told mongabay.com that QRBF has a two-prong strategy for land acquisition.

The first strategy is to secure land for the most threatened species on the planet, almost all of which, Dinerstein said, are “narrow-range endemics” like the Santa Marta parakeet.

The second strategy is to protect wide-ranging species by adding to the patchwork of protected areas within their full range, especially by purchasing “corridors” of land that connect already-protected lands and other intact habitat.

The first grant made by the QRBF, announced at its launch event in New York City in February, is a good example, Dinerstein said. It sent $45,000 to purchase habitat for the world’s northernmost population of jaguars (Panthera onca), in Sonora, Mexico, where poaching and other human activity are encroaching on its territory.

“Young males have to disperse from their natal area, they can’t stay where they were born,” Dinerstein told mongabay.com. “For them to exist in human-dominated landscapes, they need these corridors.”

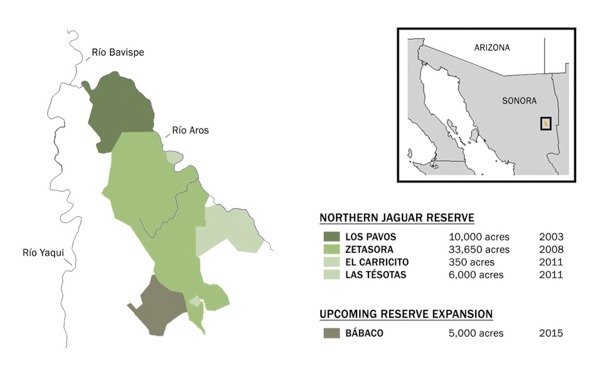

The land will add to the 50,000-acre Northern Jaguar Reserve, established by the Tucson-based NGO Northern Jaguar Project and its Mexico City-based partner, Naturalia. The groups are using the QRBF grant to buy the 5,000-acre Bábaco ranch, which connects the current reserve to another area that has historically been the center of the jaguar’s population base.

A map shows the location and extent of the Northern Jaguar Reserve in Sonora, Mexico, along with the recent addition of the Bábaco ranch. Map credit: Northern Jaguar Project / Naturalia.

A map shows the location and extent of the Northern Jaguar Reserve in Sonora, Mexico, along with the recent addition of the Bábaco ranch. Map credit: Northern Jaguar Project / Naturalia.

All proposals to the QRBF have to include plans for ongoing management and monitoring of the lands, which is one of the chief criteria the advisory panel uses to evaluate whether or not a grant is worth making, Dinerstein said. But of course, their chief goal is to make the funds available for critical acquisitions when the opportunity arises.

“The Northern Jaguar Project were guinea pigs for us,” Dinerstein explained. “I wanted to see how fast our system worked. I got the proposal on a Monday. I decided to send it out to 8 of the 55 people we have signed up on our advisory panel, just to see how fast they could respond. I set a deadline of three days with questions about the proposal, which was about five pages long. All eight reviews came back by Wednesday.” A check was handed to the Northern Jaguar Project at the launch event in NYC.

A six-month-old jaguar cub named Pedro at the Bábaco ranch, which was recently added to a jaguar reserve in Sonora, Mexico. With eleven jaguars documented and an abundant water supply, the property offers important habitat for protection, according to project leaders. Photo credit: Northern Jaguar Project / Naturalia.

A six-month-old jaguar cub named Pedro at the Bábaco ranch, which was recently added to a jaguar reserve in Sonora, Mexico. With eleven jaguars documented and an abundant water supply, the property offers important habitat for protection, according to project leaders. Photo credit: Northern Jaguar Project / Naturalia.

Among the advisors who gave the green light to the grant were two of Mexico’s leading biodiversity specialists, two of the world’s foremost jaguar experts, one expert on large carnivores in North America, two people with deep experience with Mexican NGOs, and a former editor of a major conservation biology journal, according to Dinerstein.

Libélula, the mother of the baby jaguar shown in the preceding picture, at the recently protected Bábaco ranch. Photo credit: Northern Jaguar Project / Naturalia.

Libélula, the mother of the baby jaguar shown in the preceding picture, at the recently protected Bábaco ranch. Photo credit: Northern Jaguar Project / Naturalia.

The most unique part of the QRBF, at least in Dinerstein’s experience, is that 100 percent of the funds go to the field, not to overhead for the Weeden Foundation or 1% For The Planet. This has been a major selling point for companies considering investing in conservation, Dinerstein said. It has also generated enthusiasm among the members of the advisory panel, all of who donate their time.

“These experts are excited about the project,” Dinerstein said. “A lot of their job is reviewing papers. It’s much more exciting to review proposals to buy land and save endangered species. We’re getting really good reviews.”

As most conservation biologists will agree, Dinerstein said, “real estate is the simplest and best thing you can do to conserve endangered species, and that’s what we’re about.”

Citations:

Coetzee BWT, Gaston KJ, Chown SL (2014) Local Scale Comparisons of Biodiversity as a Test for Global Protected Area Ecological Performance: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 9(8): e105824. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105824

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.